Navigating the thronging streets of Lagos, Nigeria, is a challenge at the best of times. But during the rainy seasons, the city's streets can become almost impassable. Home to more than 24 million, Lagos is Nigeria's economic powerhouse, making it a destination for people seeking new opportunities. But that rapid growth creates pressure on the streets, and the environment.

The streets are often flooded, in part due to the dysfunctional disposal of the 6,000-10,000 tonnes of rubbish generated daily in the city. After a downpour, rubbish piles up in open gutters and makes moving around the streets difficult. “I worry when it rains, especially when it is heavy,” says Lagos resident Stephanie Erigha. "It makes me anxious." On one occasion when taking a taxi through a waterlogging-prone part of the city, she recalls the water gushing right into the back seat next to her.

While the overall climate in Lagos is expected to see less rainfall overall with climate change, the intensity of rain is expected to increase, bringing with it greater risk of flooding. Meanwhile, the low-lying city is also particularly vulnerable to water from another source: rising seas. If global warming exceeds 2C, the city is predicted to see 90cm of sea level rise by 2100, according to research led by marine physicist Svetlana Jevrejeva, of the UK's National Oceanography Centre.

How, in the face of flooding, blocked streets and rising waters, is Africa's most populous city adapting?

Floating architecture

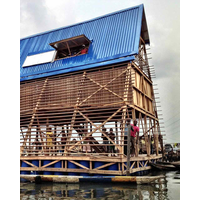

There is one part of Lagos that has extensive experience of dealing with high water. Much of the Makoko neighbourhood is not built on land, but rather sits on stilts above the waterline. Makoko, known as the "Venice of Africa", is a labyrinthine slum built on stilts and navigated by canoe. The slum has little access to electricity or clean sanitation, but it has also been home to innovations like the Makoko Floating School, a structure resting on recycled empty plastic barrels for buoyancy. The school's pyramid shape helped lower its centre of gravity and so increase its stability, while also being an ideal roof shape for shedding heavy rains.

This prototype, however, was short-lived after suffering lasting damage from a storm in 2016. But it set the precedent for floating system that its architect, Kunlé Adeyemi, would put to use in other coastal cities. Iterations of the floating structure have been built in Venice and Bruges.

Most recently, a version of the design is being constructed in the city of Mindelo on the island of São Vicente, Cape Verde. “It is a floating music hub," says Adeyemi, the founder of NLÉ, an urban design and development consultancy. "In this iteration, we are building it in a bay within the Atlantic Ocean.” The hub is made from timber and consists of three floating vessels housing a multipurpose live performance hall, a state-of-the-art recording studio and a platform for thirsty guests.

Wood, Adeyemi says, is an ideal sustainable material for building floating structures. “If you have a cost-benefit metrics of different solutions for building on water, wood will be very high in ratings,” he says.

The floating music hub is part of NLÉ’s African Water Cities project, which seeks to find new ways for waterfront communities to live with rising sea levels. Instead of fighting water, says Adeyemi, we want to learn to live with it.

Water traffic

It only took one ferry journey for Lagos resident Olajumoke Oyelese, to be "hooked". The speed of travel possible on a ferry far outstripped what she was used to idling in traffic on Lagos' roads.

Oluwadamilola Emmanuel, general manager of the Lagos State Waterways Authority, says that water transport in the city has come a long way in terms of coverage. According to Emmanuel, now there are more than 42 ferry routes on the waterways with 30 commercial jetties and terminals spanning across three districts.

Besides the city authorities, an increasing number of firms are setting up water transport businesses in the city. In 2019, Uber set sail with the pilot-run of its Uber Boat service. The goal was to ease the city's infamous road congestion. "We are aware of the man-hours and productivity that are lost every day due to road traffic in Lagos state," says Lorraine Onduru, a spokesperson for the company. "[We] are looking at ways to provide commuters with an easy and affordable way to get in and out of the city's business districts."

For the entire story with illustrations, visit the BBC website: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210121-lagos-nigeria-how-africas-largest-city-is-staying-afloat